CLYDE DALTON RUTLEDGE

Malvern Leader

Thursday, August 11, 1966

1881st AVIATION BATTALION ENGINEERS

FROM

CORPS OF ENGINEERS: THE WAR AGAINST JAPAN

Pages 529-531

Hollandia—Assault

RECKLESS Task Force, together with its supporting Allied naval and air units, constituted the largest assemblage of ships, planes, and men organized for any operation in the Southwest Pacific up to this time. Commanded by General Eichelberger, and assigned the mission of seizing the Hollandia area and initiating construction of BASE G, RECKLESS Task Force included the 24th and 41st Divisions (the latter less the 163d RCT) and twenty-eight attached combat and service units, totaling approximately 60,000 men. The engineer component amounted to about 41 percent, the highest for an amphibious operation so far conducted in the Southwest Pacific; most of this percentage represented construction units. By mid-April, prepartions for the assault were complete. The 24th Division staged at Goodenough Island, 1,000 miles from Hollandia; the 41st Division, at Finschhafen, 700 miles from the objective area. The naval convoys carrying these two divisions and their supporting units sailed for the Admiralties, which they reached the first night; thereupon, the combined task force turned westward. ([1] RECKLESS Task Force, Hist of the Hollandia Opn, pp. 5-6. [2] Maj R. M. Little, 1st Aust Corps, Rpt on Engr Opns at Hollandia and Aitape, Dutch New Guinea, 22 Apr-4 May 44. SWPA File 128.)

On the morning of 22 April under excellent sea and weather conditions, the assault was made as scheduled. The 2d Brigade’s support battery was active. Besides its 4 rocket LCVP’s, 4 rocket Dukws, and 2 flak LCM’s, the battery had 43 Buffaloes to carry troops across reefs and shallow waters near the beaches. The battery’s craft were about equally divided for the two assaults. When the naval bombardment ceased, rocket LCVP’s and Dukw’s and flak LCM’s mov3ed to about 100 yards from shore and loosed their barrages on the beaches. Waves of landing craft brought in troops and supplies. (2d ESB, Monthly Hist Rpt of Opns, Apr 1-30, SWPA File E-20-4.)

The 532d Boat and Shore Regiment, less two companies, landed men and supplies for the 41st Division on the three White Beaches at Humboldt Bay. Only a few of the amphibian craft, upon approaching shore, were hit by enemy rifle fire; most of the Japanese had fled inland. Ships had to be unloaded on D-day so that they could get away that night; stacked higher and higher on the beaches, supplies were in a vulnerable position. At Tanahmerah, the 542d Boat and Shore Regiment helped land the 24th Division on Red Beaches 1 and 2. Except for random rifle fire, enemy interference was lacking. As at Humboldt Bay, complications began when supplies piled up on shore. As intelligence reports had indicated, the beaches were narrow; to the rear were mangrove swamps, some of which had not shown up on aerial photographs because of the dense growth of trees in the water. Exits were far more restricted than had been anticipated. Red Beach 2 had such an extensive swamp in back of it that moving supplies into the interior was out of the question; during the first night, large amounts were shuttled across Tanahmerah Bay to the other beach. Nor did everything go smoothly at Humboldt Bay. ([1] 532d EBSR, Unit Rpt No. 5, 15 Mar-7 June 44. SWPA Files. [2] RECKLESS Task Force, Hist of the Hollandia Opn, p. 54. [3] Heavey, Down Ramp!, pp. 116-17. [4] Ltr. Heavey to Reybold, 30 Jun 44. SWPA File 73.) A lone Japanese plane coming over on the second day dropped a number of bombs near an ammunition dump. For three days explosions rocked the area, and fires raged out of control. The amphibian boatmen, bringing their craft close to shore, rescued many of the men trapped on the beaches by the flames.

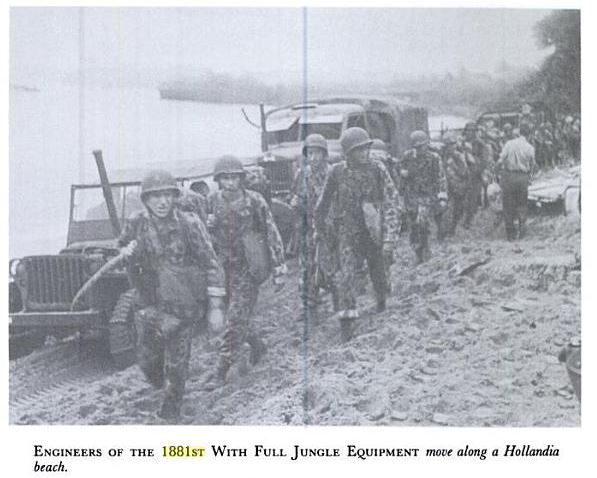

Soon after the first landings, the combat engineers began to advance inland with the infantry. The 116th Combat Battalion (less Company A) of the 41st Division came ashore at Humboldt Bat on D-day. Enemy resistance was negligible. The men widened the trail leading from the beaches to the native village of Pim, making it passable for trucks. They then began to improve a Japanese-built road running from Pim to the airdromes. This road, which intelligence sources had indicated was in fair condition, turned out to be little better than a trail, which at most could take 2 ½-ton trucks in dry weather. In swampy areas it became a quagmire largely because of the heavy, continuous traffic. The 116th engineers, helped by the 79th Combat and the 1881st Aviation Battalions, had to make a major effort on this road. (Rpt, Col Herbert G. Lauterbach, CO 116th Engr Combat Bn, to Krueger, 28 Jun 44. SWPA Files.) At Tanahmerah Bay the 3d Combat Battalion (less Company B) of the 24th Division landed on D-day. The effort required to support the infantry in the advance to the airdromes was more laborious than at Humboldt Bay. The Trail leading inland was too narrow and steep even for jeeps. For days, the men had to carry supplies forward. Added to these difficulties were the rains, which began on the second day of the landing, the lack of gravel or rock for surfacing, the inadequate number of hand tools, and the small number of natives in the region willing to work. The most favorable element was the ineffectual enemy resistance. By 26 April the three airdromes were in American hands. ([1] Tanahmerah Bay Landing Force, Hist Rpt. SWPA Files. [2] 3d Engr Combat Bn, Hist Rpt, an. 1. [3] USAFFE Bd Rpt 31.)

As soon as the infantry reached the airfields—named Sentani, Cyclops, and Hollandia—the engineers began the job of rebuilding them. The three runways, satisfactorily located, considering the terrain, were poorly constructed; they were of earth, and drainage was inadequate. The subbase at Sentani was so poor that the Japanese had placed the runway surfacing on bamboo matting. Allied bombings had damaged the fields heavily. Four aviation battalions, working under the direction of headquarters, 931st Aviation Regiment, began the job of reconstruction. The aviation engineers’ main job was to find a suitable material for surfacing. In nearby streams they came upon sufficient quantities of rock and gravel. They graded the Sentani and Cyclops runways and placed crushed rock to a depth of about six inches; after rolling the rock into a compact layer, they dampened it slightly and topped it first with an asphalt cutback and then with a coat of pure asphalt and limestone chips. They surfaced the Hollandia runway with iron ore which they took from a nearby deposit, mixing the ore with equal parts of sand. The most troublesome job was providing adequate drainage. The water table was high because of the many swamps and streams. The men dug three-foot deep ditches, which helped considerably to lower the ground water level. On the whole, the work of making the airdromes serviceable progressed rapidly, despite the terrain, which was poorer than expected. By 29 April 4,000 feet of the Cyclops runway was ready for dry-weather use by transports, and by 3 May the Hollandia strip had been completed to 5,000 feet and a squadron of fighters was stationed there. ([1] Dudley and Staggs, “Engineer Troops on Airdrome Construction,” The Military Engineer, XXXVII (October, 1945), 386-88. [2] Engrs of SWPA, VI, 230. [3] Eichelberger, Our Jungle Road to Tokyo, p. 113.)

The unsatisfactory roads in the Hollandia area made it hard to get supplies to the airfields and the area around them where the base was being constructed. Japanese-built Tami airfield near the coast southeast of Humboldt Bay, if improved, could be used to airlift supplies into the interior. Accordingly, General Krueger directed the engineers to lengthen the grass runway at Tami to 4,000 feet and surface it with steel mat. By 3 May the engineers had improved the strip sufficiently to make landings and takeoffs by C-47’s possible. In the next few days C-47’s made almost 500 trips from Tami to the fields at Hollandia, bringing in gasoline, supplies, and troops. Useful in the early days of the Hollandia operation, Tami was not further developed because of its swampy location. ([1] Craven and Cate, eds., Guadalcanal to Saipan, pp. 609-10.)

On the morning of 22 April under excellent sea and weather conditions, the assault was made as scheduled. The 2d Brigade’s support battery was active. Besides its 4 rocket LCVP’s, 4 rocket Dukws, and 2 flak LCM’s, the battery had 43 Buffaloes to carry troops across reefs and shallow waters near the beaches. The battery’s craft were about equally divided for the two assaults. When the naval bombardment ceased, rocket LCVP’s and Dukw’s and flak LCM’s mov3ed to about 100 yards from shore and loosed their barrages on the beaches. Waves of landing craft brought in troops and supplies. (2d ESB, Monthly Hist Rpt of Opns, Apr 1-30, SWPA File E-20-4.)

The 532d Boat and Shore Regiment, less two companies, landed men and supplies for the 41st Division on the three White Beaches at Humboldt Bay. Only a few of the amphibian craft, upon approaching shore, were hit by enemy rifle fire; most of the Japanese had fled inland. Ships had to be unloaded on D-day so that they could get away that night; stacked higher and higher on the beaches, supplies were in a vulnerable position. At Tanahmerah, the 542d Boat and Shore Regiment helped land the 24th Division on Red Beaches 1 and 2. Except for random rifle fire, enemy interference was lacking. As at Humboldt Bay, complications began when supplies piled up on shore. As intelligence reports had indicated, the beaches were narrow; to the rear were mangrove swamps, some of which had not shown up on aerial photographs because of the dense growth of trees in the water. Exits were far more restricted than had been anticipated. Red Beach 2 had such an extensive swamp in back of it that moving supplies into the interior was out of the question; during the first night, large amounts were shuttled across Tanahmerah Bay to the other beach. Nor did everything go smoothly at Humboldt Bay. ([1] 532d EBSR, Unit Rpt No. 5, 15 Mar-7 June 44. SWPA Files. [2] RECKLESS Task Force, Hist of the Hollandia Opn, p. 54. [3] Heavey, Down Ramp!, pp. 116-17. [4] Ltr. Heavey to Reybold, 30 Jun 44. SWPA File 73.) A lone Japanese plane coming over on the second day dropped a number of bombs near an ammunition dump. For three days explosions rocked the area, and fires raged out of control. The amphibian boatmen, bringing their craft close to shore, rescued many of the men trapped on the beaches by the flames.

Soon after the first landings, the combat engineers began to advance inland with the infantry. The 116th Combat Battalion (less Company A) of the 41st Division came ashore at Humboldt Bat on D-day. Enemy resistance was negligible. The men widened the trail leading from the beaches to the native village of Pim, making it passable for trucks. They then began to improve a Japanese-built road running from Pim to the airdromes. This road, which intelligence sources had indicated was in fair condition, turned out to be little better than a trail, which at most could take 2 ½-ton trucks in dry weather. In swampy areas it became a quagmire largely because of the heavy, continuous traffic. The 116th engineers, helped by the 79th Combat and the 1881st Aviation Battalions, had to make a major effort on this road. (Rpt, Col Herbert G. Lauterbach, CO 116th Engr Combat Bn, to Krueger, 28 Jun 44. SWPA Files.) At Tanahmerah Bay the 3d Combat Battalion (less Company B) of the 24th Division landed on D-day. The effort required to support the infantry in the advance to the airdromes was more laborious than at Humboldt Bay. The Trail leading inland was too narrow and steep even for jeeps. For days, the men had to carry supplies forward. Added to these difficulties were the rains, which began on the second day of the landing, the lack of gravel or rock for surfacing, the inadequate number of hand tools, and the small number of natives in the region willing to work. The most favorable element was the ineffectual enemy resistance. By 26 April the three airdromes were in American hands. ([1] Tanahmerah Bay Landing Force, Hist Rpt. SWPA Files. [2] 3d Engr Combat Bn, Hist Rpt, an. 1. [3] USAFFE Bd Rpt 31.)

As soon as the infantry reached the airfields—named Sentani, Cyclops, and Hollandia—the engineers began the job of rebuilding them. The three runways, satisfactorily located, considering the terrain, were poorly constructed; they were of earth, and drainage was inadequate. The subbase at Sentani was so poor that the Japanese had placed the runway surfacing on bamboo matting. Allied bombings had damaged the fields heavily. Four aviation battalions, working under the direction of headquarters, 931st Aviation Regiment, began the job of reconstruction. The aviation engineers’ main job was to find a suitable material for surfacing. In nearby streams they came upon sufficient quantities of rock and gravel. They graded the Sentani and Cyclops runways and placed crushed rock to a depth of about six inches; after rolling the rock into a compact layer, they dampened it slightly and topped it first with an asphalt cutback and then with a coat of pure asphalt and limestone chips. They surfaced the Hollandia runway with iron ore which they took from a nearby deposit, mixing the ore with equal parts of sand. The most troublesome job was providing adequate drainage. The water table was high because of the many swamps and streams. The men dug three-foot deep ditches, which helped considerably to lower the ground water level. On the whole, the work of making the airdromes serviceable progressed rapidly, despite the terrain, which was poorer than expected. By 29 April 4,000 feet of the Cyclops runway was ready for dry-weather use by transports, and by 3 May the Hollandia strip had been completed to 5,000 feet and a squadron of fighters was stationed there. ([1] Dudley and Staggs, “Engineer Troops on Airdrome Construction,” The Military Engineer, XXXVII (October, 1945), 386-88. [2] Engrs of SWPA, VI, 230. [3] Eichelberger, Our Jungle Road to Tokyo, p. 113.)

The unsatisfactory roads in the Hollandia area made it hard to get supplies to the airfields and the area around them where the base was being constructed. Japanese-built Tami airfield near the coast southeast of Humboldt Bay, if improved, could be used to airlift supplies into the interior. Accordingly, General Krueger directed the engineers to lengthen the grass runway at Tami to 4,000 feet and surface it with steel mat. By 3 May the engineers had improved the strip sufficiently to make landings and takeoffs by C-47’s possible. In the next few days C-47’s made almost 500 trips from Tami to the fields at Hollandia, bringing in gasoline, supplies, and troops. Useful in the early days of the Hollandia operation, Tami was not further developed because of its swampy location. ([1] Craven and Cate, eds., Guadalcanal to Saipan, pp. 609-10.)