MARTIN LEE "BUTCH" GILLFILLAN

U.S. regimental flag of the 168th Iowa. World War I. Governmental Issue. 1 layer. Machine sewn. Field is composed of dark blue, silk panel. At center is an embroidered design of a brown Federal eagle with a cache of arrows in one talon and an olive branch in the other. A yellow Federal motto "E PLURBIS UNUM" ribbon is in eagle's beak. Above, located in a white cloud shape, is a dark blue circle outlined in rays of yellow sunshine and contains 13 5-pointed, white embroidered stars. Below the eagle is a red embroidered, swallowtail unit ID ribbon with "168TH/U.S./INFANTRY" embroidered in white. Top, bottom and fly edges of the field are selvedge edges. Top, bottom and fly end

Alphabetical Listing

Conflict

Find A Grave

Iowa Gravestone

Service Branch

Company M, 168th Iowa at St. Mihiel 1918

Gen. MacArthur and the 168th

Conflict

Find A Grave

Iowa Gravestone

Service Branch

Company M, 168th Iowa at St. Mihiel 1918

Gen. MacArthur and the 168th

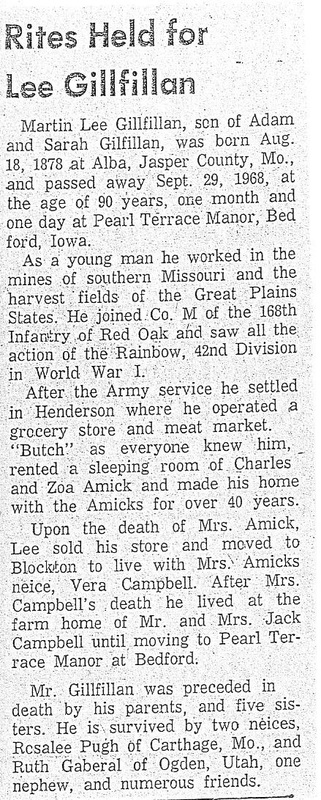

OBITUARY

From People of Note @ Croix Rouge Farm Memorial Foundation

Bennett, Colonel Ernest R.

Commander of the 168th (Iowa) Infantry Regiment from mobilization until the heights of the Ourcq River. He was relieved on July 29, 1918 during the fighting there and replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Mathew W. Tinley.

Donovan, Lieutenant Colonel William H. “Wild Bill”

A battalion commander of the 165th (New York) Infantry Regiment of the “Rainbow”, he was on the point of the regiment’s unsuccessful attack on the Kriemhilde Stellung on the eastern flank of the 167th (Alabama). That regiment and the 168th (Iowa) attacked the Cote de Chatillon at the strongest point of the four German lines of defense making the Hindenburg Line. After two days of fighting, Donovan was wounded before falling back on October 15, 1918, gaining him a nomination for the Congressional Medal of Honor. Donovan went on to become the World War II commander of the Office of Strategic Services and founder of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Fallaw, Captain Thomas H.

Became I Company commander, organized, directed and carried through to successful conclusion all of the 167th (Alabama) front line activities at the Cote de Chatillon on October 16, 1918. With a provisional group of about 120 men, all that were left from the 3rd Battalion, he moved under cover of darkness to the west of the hill, reaching the attack position at 6:10 a.m. At about 10:00 a.m. the 151st (Georgia) Machine Gun Battalion fired for 30 minutes into the fortified German position, then lifted fire for 15 minutes to cover the German held crest and reverse slope. Fallaw and his men jumped off to the north and east from their position on the west side of the Côte. After the wild attack of his force, there were two German counterattacks. Elements of the 168th (Iowa) then converged on the hill at the same time as the Alabama forces and the position was taken by 4:00 p.m. with equal honors for all. Captain Fallaw was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross. He had served as a sergeant on the Mexican Border and was commissioned before going to France.

Winn, Major Cooper D., Jr.(see website)

Commanded the 151st (Georgia) Machine Gun Battalion at the Côte de Châtillon, reporting directly to the 84th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur. Winn personally assigned targets to 65 machine guns placed on the forward slope of Hill 263 prior to the October 16, 1918 attack by the 167th (Alabama) on the Côte. At about 10:00 a.m. his guns commenced indirect and enfilade (down into) firing for 30 minutes into the fortified German position, then lifted fire for 15 minutes to cover the crest and reverse slope. When the moving fire lifted, the assault force of about 120 men from the 3rd Battalion of the 167th (Alabama) Infantry Regiment jumped off and attacked to the north and east.from the west side of the Côte. Due to the supporting machine gun fire, the attacking infantry had less resistance and fewer casualties than anticipated. There were two German counterattacks. Elements of the 168th (Iowa) converged on the hill at the same time as the Alabama forces and the position was taken by 4:00 p.m. with equal honors for the two regiments. Brigadier General MacArthur cited Winn for honors and recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross, a combat award. It was not approved, but Winn received a Distinguished Service Medal and promotion to Lieutenant Colonel.

Commander of the 168th (Iowa) Infantry Regiment from mobilization until the heights of the Ourcq River. He was relieved on July 29, 1918 during the fighting there and replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Mathew W. Tinley.

Donovan, Lieutenant Colonel William H. “Wild Bill”

A battalion commander of the 165th (New York) Infantry Regiment of the “Rainbow”, he was on the point of the regiment’s unsuccessful attack on the Kriemhilde Stellung on the eastern flank of the 167th (Alabama). That regiment and the 168th (Iowa) attacked the Cote de Chatillon at the strongest point of the four German lines of defense making the Hindenburg Line. After two days of fighting, Donovan was wounded before falling back on October 15, 1918, gaining him a nomination for the Congressional Medal of Honor. Donovan went on to become the World War II commander of the Office of Strategic Services and founder of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Fallaw, Captain Thomas H.

Became I Company commander, organized, directed and carried through to successful conclusion all of the 167th (Alabama) front line activities at the Cote de Chatillon on October 16, 1918. With a provisional group of about 120 men, all that were left from the 3rd Battalion, he moved under cover of darkness to the west of the hill, reaching the attack position at 6:10 a.m. At about 10:00 a.m. the 151st (Georgia) Machine Gun Battalion fired for 30 minutes into the fortified German position, then lifted fire for 15 minutes to cover the German held crest and reverse slope. Fallaw and his men jumped off to the north and east from their position on the west side of the Côte. After the wild attack of his force, there were two German counterattacks. Elements of the 168th (Iowa) then converged on the hill at the same time as the Alabama forces and the position was taken by 4:00 p.m. with equal honors for all. Captain Fallaw was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross. He had served as a sergeant on the Mexican Border and was commissioned before going to France.

Winn, Major Cooper D., Jr.(see website)

Commanded the 151st (Georgia) Machine Gun Battalion at the Côte de Châtillon, reporting directly to the 84th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur. Winn personally assigned targets to 65 machine guns placed on the forward slope of Hill 263 prior to the October 16, 1918 attack by the 167th (Alabama) on the Côte. At about 10:00 a.m. his guns commenced indirect and enfilade (down into) firing for 30 minutes into the fortified German position, then lifted fire for 15 minutes to cover the crest and reverse slope. When the moving fire lifted, the assault force of about 120 men from the 3rd Battalion of the 167th (Alabama) Infantry Regiment jumped off and attacked to the north and east.from the west side of the Côte. Due to the supporting machine gun fire, the attacking infantry had less resistance and fewer casualties than anticipated. There were two German counterattacks. Elements of the 168th (Iowa) converged on the hill at the same time as the Alabama forces and the position was taken by 4:00 p.m. with equal honors for the two regiments. Brigadier General MacArthur cited Winn for honors and recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross, a combat award. It was not approved, but Winn received a Distinguished Service Medal and promotion to Lieutenant Colonel.

From Iowa State University

Digital Repository @ Iowa State University

Graduate Theses and Dissertations

Graduate College

2012

Ensuring Survival: How Mexican Border Service

and World War I was Vital for the Survival of the

National Guard System

Matthew Margis

Iowa State University

PAGES 31-36

Conscripted troops did not make up most of the AEF. Volunteerism was still a leading factor in raising the American Army, and nowhere was the spirit of volunteerism more prevalent and long-standing than in the National Guard. On March 25, President Wilson recalled into federal service a small number of guardsmen from each state in preparation for a possible European war, and by July 15, 1917 all of the National Guard had been called into federal service. Guardsmen reported to their respective duty stations over the course of the next two weeks, and on August 5, 1917 the government officially removed the Guard from state control. (103) Within months of the declaration of war, the National Guard

had become part of the AEF, and the Guard did a more efficient job of quickly providing

trained units for service than could the National Army, which struggled to organize and train

large numbers of raw conscripted men.

Border duty prepared the troops for service, and ensured their quick mobilization. However, not all of the troops who returned from the border remained in the Guard due to their refusal to take a second oath of service. For instance, only 2,200 Iowa troops out of the 4,300 Iowa Guardsmen who returned from the border agreed to take the oath; yet, these troops were more prepared for service than new volunteers and those drafted into service. (104) Essentially, the 2,200 troops who remained after the border duty were reorganized and moved into the 3rd Iowa Infantry, which was renamed the 168th U.S. Infantry and became part of the 42nd Infantry Division (or the Rainbow Division, made up primarily of Guardsmen from across the nation who returned from the border), which was one of the first divisions to arrive in France. (105) The 168th was mobilized in April of 1917, and by mid-October, the unit had received orders to go “over there.” (106) Because the guardsmen were already trained, the Rainbow Division was able to arrive in France along with the first regular army troops.

A small number of guardsmen who continued serving after the Mexican border conflict and were not transferred to the Rainbow Division provided valuable guidance for the new recruits just joining the guard. These units with untrained recruits required more time for preparation, and the military assigned them to extended duty at the home front. For instance, the first battalion of Iowa’s Field Artillery was sent to Fort Roots near Little Rock, Arkansas and later to Camp Cody, New Mexico. The field artillery was later joined at Camp Cody by the rest of the newly organized Iowa Guard units as part of the 34th Infantry Division. (107) The Illinois Guard not included in the Rainbow Division formed the 33rd Infantry Division and moved to Camp Logan near Houston, Texas for advanced training. (108) Many of these troops did not receive overseas orders for nearly another year. While this experience was similar to that of conscripted troops, it was also shared by new volunteers of the regular army. Therefore, guardsmen who did not participate in the border duty were as prepared for overseas duty as new volunteers.

After a long journey, the troops finally arrived in Europe, but did not head immediately to the front lines. The first stop was a short layover in England, where the men underwent further drills. American troops received a welcome and motivational letter from King George V, who offered his support and thanks to the American soldiers. (109) Many men enjoyed their brief time in England, such as Iowa guardsman August Smidt who remarked in a letter to his girlfriend that his stay was in a “very good place, also good mess, but I think we will be leaving here before very long, but this is sure a beautiful country.” (110)

Upon leaving England for France, guardsmen spent more time drilling and training for the front. For instance, the 168th Infantry arrived at La Havre on December 9, 1917 and moved to a rest camp, which Cecil Clark described as a “Hell hole.” (111) Two days later, the troops moved out at dawn for Rimencourt, when they had the pleasure of passing Versailles. The troops stayed in Rimencourt for over a month, where they spent their time drilling and undergoing inspections. Finally, on February 1, 1918, after nearly two months in France, the troops of the 168th hiked toward the front lines. Throughout February these troops spent their days maneuvering, hiking, and parading through the streets of France for official reviews. However, the lives of these troops changed forever in March. Cecil Clark noted in his diary that the Germans raided two sister companies on March 5. He further noted that Company M along with two French companies went “over the top” on March 11, where an Iowa corporal was killed. The next week was filled with German artillery barrages, and on the March 17 Clark’s company made their first raid against the German lines. (112)

Sergeant Charles Kosek was also in the trenches during the first weeks of March, 1918, and his highly personalized diary entries noted the strains and emotions of wartime. Kosek perceived a level of hypocrisy on the part of commanders. According to Kosek, a company of the 168th had been awarded war crosses even though they were a mile in the rear of the trenches. Conversely, “We ran out and repulsed the Hun attack as soon as the barrage lifted; we got nothing. B Co. waited till they were sure it was all over and when they came out the Huns were in their trench and they had to run them out, result they got three medals.” (113) While this account probably contains levels of truth, it is also partial and B Company troops likely maintained a different opinion. Private Alfred Bowen stated in a letter, “You really cannot believe anything you hear in the army, as you hear all kinds of conflicting rumors." (114)

World War I served as an eye-opening experience for Guard troops, because guardsmen never saw actual combat at the border. The realities of trench warfare and modern weaponry created devastation, destruction, and pain foreign to most young troopers, but border duty lessened the learning curve, as guardsmen already held the basic skills necessary for combat. Further, the war changed the way many saw warfare, erasing what many admired in retrospect as the old spirit and glory of war. Indeed, Marinetti’s call to glorify war was put to the test. Life in the trenches, which consisted of constant shelling, machine gun fire, mortar attacks, air and tank warfare, and the painful reality of gas warfare replaced pre-war ideas of heroism. As Paul Fussell argues, “Every war is ironic because every war is worse than expected.” (115) The Guard troops, particularly those in the Rainbow Division, soon faced this reality in daily combat actions, but they were extensively trained for combat operations.

Of the new weaponry of the First World War, perhaps none was as devastating as the effects of poisonous gas on the soldiers in the trenches. Soldiers had some protection, including gas masks, which they tested in specially designed chambers to the rear of the trenches. (116) But even gas masks could not ensure safety; Iowa Guardsman Lloyd Ross, who was a Captain during World War I in the 168th and a veteran of the Spanish-American War, noted on one occasion that after seeing gas pouring into his trench, he gave the call of “gas” to warn others before putting on his mask. The result was incredibly painful.

I could feel the gas burning my throat and lungs and then I knew that I didn’t get my

mask on in time and that I was gassed. I stood my post for a few minute and then I

began to get dizzy and couldn’t stand up anymore. Corporal Kelly took me to my

bunk and tole me not to move around. The next morning I was taken to the hospital

where I found several of my pals who were gassed the same night. (117)

Francis Webster, who was also a member of the 168th Infantry, noted in a letter to his parents, that he had also been gassed and was recuperating in a hospital. (118)

While the Guard troops of the 42nd Division saw extensive combat in Europe, much of the National Guard did not share this experience. The Rainbow Division saw action in every major U.S. engagement of the war, and it included Guard troops and officers from 26 total states and included many distinguished officers such as then Colonel Douglas MacArthur. (119) However, most guardsmen involved in combat operations did not arrive in France until the middle of 1918; yet, seven of the eleven divisions poised for an American advance in August were Guard divisions. (120) Other Guard divisions, such as the 34th (containing Iowa’s Guard) were not sent directly to the front, but did see some combat as reserve organizations. (121) Unlike the wartime experience of troops in the Rainbow Division, monotony exemplified life at the camps and away from the front lines, and border duty familiarized officers and troops with the monotonous lifestyle associated with camp life away from the front lines.

The monotony of camp life is apparent in the official history of the 126th Field Artillery (formerly the First Iowa Field Artillery). The 126th arrived at Fort Roots, Arkansas early in July 1917 and left for Camp Cody, New Mexico in October 1917. The official history then noted months on end which consisted of “usual camp duties.” (122) The 126th remained at Camp Cody until July 1918, when they embarked for training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, which continued for three months. The 126th arrived in France on October 18, 1918 where they once again “took up usual camp duties.” (123) The monotony of usual camp duties was seemingly only interrupted for transportation to other stations, training of a specific nature, and official reviews of the 34th Division. (124) The experience of these Iowa troops was drastically different than those of the 168th who were actively engaged in combat; however, their service was still important to the war effort because these troops provided the regular army with the reserve force necessary to carry out combat operations.

(103) Lasher, Report, 1918, 7 and Hill, Minute Man, 262-3. Though the Guard was federalized in July, it was not until August 5 when the Guard was officially drafted into the Army as it fit under the Selective Service Act. Guardsmen removed state affiliations from uniforms and replaced them with U.S. Army insignia, and Guard units were re-numbered from state regiments to national ones to fit into the new American Army.

(104) Lasher, Report, 1918, 43. Many troops who had been stationed at the border were denied active duty status during their tour in Texas, and were required to take a third oath of service. Many guardsmen refused this third oath and left the guard. Many of these who refused to take the oath were required to enroll in the selective service and were eventually drafted into the AEF.

(105) Ibid., 33.

(106) Pvt. Everett Wright, Journal, October 19, 1917, Papers of Everett Wright, 1999.33.2 Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(107) Lasher, Report, 1918, 38. and “History of Battery ‘C’ 126th Field Artillery”

(108) Adjutant General’s Report, Roster of National Guard and Naval Militia as Called for World War Service (Springfield: Illinois State Government Press, 1918) ix and Hill, Minute Man, 272 and Paxson, America at War, 316.

(109) King George V, Letter to American Troops, January, 1918, Papers of August Smidt, Correspondence, 4: 1995.131, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(110) August Smidt, Letter to Agnes, Oct 1918, Papers of August Smidt, 4: 1995.131, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(111) Cecil A. Clark Diary, December 9, 1917, Diary of Cecil A. Clark, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(112) Cecil Clark, Diary, February to March, 1918.

(113) John Kosek, editor, The Iowa Boys: A Remembrance of a Killing Contest, The Diary and Letters of Sergeant Charles Kosek Company D, 168th Iowa Infantry, 42nd Rainbow Division, American Expeditionary Force France, 1917-1918 (Copyright, Las Vegas NV 2010: Iowa National Guard Archives) 13.

(114) Alfred Bowen, Letter to Alice Woolston, July 10, 1917, Papers of Alfred Bowen, 2000.48.4, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(115) Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975) 7.

(116) Cecil Clark, Diary, May 22, 1918.

(117) General Lloyd D. Ross, Report: Fifty Germans and How They Fared, June 1918, Papers of General Ross, WWI Box, 1999.113, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(118) Francis Webster, Collection of Sympathy Letters, November 1918, Papers and Items of Pvt. Francis Webster, 2005.107.30, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA). Webster was unfortunately killed only weeks before the official end of the war.

(119) Zieger, 107-8 and 42nd Division Headquarters “General Orders No 22.” Issued by Major General Menoher and written by Colonel Douglas MacArthur, Chief of Staff, Documents of General Ross, WWI Box, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge IA (Johnston, IA).

(120) Paxson, America at War, 341.

(121) Lasher, Report, 1918, 33-4. It should be noted that some of the troops from Camp Cody did eventually see line duty after being transferred out of their original units to supplement other National Guard and Army units already in the trenches.

(122) “History of Battery ‘C’ 126th Field Artillery, June, 1917” Kershenski Box, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA) 1.

(123) “History of Battery C,” 1-2. 124 Ibid., 1.

Border duty prepared the troops for service, and ensured their quick mobilization. However, not all of the troops who returned from the border remained in the Guard due to their refusal to take a second oath of service. For instance, only 2,200 Iowa troops out of the 4,300 Iowa Guardsmen who returned from the border agreed to take the oath; yet, these troops were more prepared for service than new volunteers and those drafted into service. (104) Essentially, the 2,200 troops who remained after the border duty were reorganized and moved into the 3rd Iowa Infantry, which was renamed the 168th U.S. Infantry and became part of the 42nd Infantry Division (or the Rainbow Division, made up primarily of Guardsmen from across the nation who returned from the border), which was one of the first divisions to arrive in France. (105) The 168th was mobilized in April of 1917, and by mid-October, the unit had received orders to go “over there.” (106) Because the guardsmen were already trained, the Rainbow Division was able to arrive in France along with the first regular army troops.

A small number of guardsmen who continued serving after the Mexican border conflict and were not transferred to the Rainbow Division provided valuable guidance for the new recruits just joining the guard. These units with untrained recruits required more time for preparation, and the military assigned them to extended duty at the home front. For instance, the first battalion of Iowa’s Field Artillery was sent to Fort Roots near Little Rock, Arkansas and later to Camp Cody, New Mexico. The field artillery was later joined at Camp Cody by the rest of the newly organized Iowa Guard units as part of the 34th Infantry Division. (107) The Illinois Guard not included in the Rainbow Division formed the 33rd Infantry Division and moved to Camp Logan near Houston, Texas for advanced training. (108) Many of these troops did not receive overseas orders for nearly another year. While this experience was similar to that of conscripted troops, it was also shared by new volunteers of the regular army. Therefore, guardsmen who did not participate in the border duty were as prepared for overseas duty as new volunteers.

After a long journey, the troops finally arrived in Europe, but did not head immediately to the front lines. The first stop was a short layover in England, where the men underwent further drills. American troops received a welcome and motivational letter from King George V, who offered his support and thanks to the American soldiers. (109) Many men enjoyed their brief time in England, such as Iowa guardsman August Smidt who remarked in a letter to his girlfriend that his stay was in a “very good place, also good mess, but I think we will be leaving here before very long, but this is sure a beautiful country.” (110)

Upon leaving England for France, guardsmen spent more time drilling and training for the front. For instance, the 168th Infantry arrived at La Havre on December 9, 1917 and moved to a rest camp, which Cecil Clark described as a “Hell hole.” (111) Two days later, the troops moved out at dawn for Rimencourt, when they had the pleasure of passing Versailles. The troops stayed in Rimencourt for over a month, where they spent their time drilling and undergoing inspections. Finally, on February 1, 1918, after nearly two months in France, the troops of the 168th hiked toward the front lines. Throughout February these troops spent their days maneuvering, hiking, and parading through the streets of France for official reviews. However, the lives of these troops changed forever in March. Cecil Clark noted in his diary that the Germans raided two sister companies on March 5. He further noted that Company M along with two French companies went “over the top” on March 11, where an Iowa corporal was killed. The next week was filled with German artillery barrages, and on the March 17 Clark’s company made their first raid against the German lines. (112)

Sergeant Charles Kosek was also in the trenches during the first weeks of March, 1918, and his highly personalized diary entries noted the strains and emotions of wartime. Kosek perceived a level of hypocrisy on the part of commanders. According to Kosek, a company of the 168th had been awarded war crosses even though they were a mile in the rear of the trenches. Conversely, “We ran out and repulsed the Hun attack as soon as the barrage lifted; we got nothing. B Co. waited till they were sure it was all over and when they came out the Huns were in their trench and they had to run them out, result they got three medals.” (113) While this account probably contains levels of truth, it is also partial and B Company troops likely maintained a different opinion. Private Alfred Bowen stated in a letter, “You really cannot believe anything you hear in the army, as you hear all kinds of conflicting rumors." (114)

World War I served as an eye-opening experience for Guard troops, because guardsmen never saw actual combat at the border. The realities of trench warfare and modern weaponry created devastation, destruction, and pain foreign to most young troopers, but border duty lessened the learning curve, as guardsmen already held the basic skills necessary for combat. Further, the war changed the way many saw warfare, erasing what many admired in retrospect as the old spirit and glory of war. Indeed, Marinetti’s call to glorify war was put to the test. Life in the trenches, which consisted of constant shelling, machine gun fire, mortar attacks, air and tank warfare, and the painful reality of gas warfare replaced pre-war ideas of heroism. As Paul Fussell argues, “Every war is ironic because every war is worse than expected.” (115) The Guard troops, particularly those in the Rainbow Division, soon faced this reality in daily combat actions, but they were extensively trained for combat operations.

Of the new weaponry of the First World War, perhaps none was as devastating as the effects of poisonous gas on the soldiers in the trenches. Soldiers had some protection, including gas masks, which they tested in specially designed chambers to the rear of the trenches. (116) But even gas masks could not ensure safety; Iowa Guardsman Lloyd Ross, who was a Captain during World War I in the 168th and a veteran of the Spanish-American War, noted on one occasion that after seeing gas pouring into his trench, he gave the call of “gas” to warn others before putting on his mask. The result was incredibly painful.

I could feel the gas burning my throat and lungs and then I knew that I didn’t get my

mask on in time and that I was gassed. I stood my post for a few minute and then I

began to get dizzy and couldn’t stand up anymore. Corporal Kelly took me to my

bunk and tole me not to move around. The next morning I was taken to the hospital

where I found several of my pals who were gassed the same night. (117)

Francis Webster, who was also a member of the 168th Infantry, noted in a letter to his parents, that he had also been gassed and was recuperating in a hospital. (118)

While the Guard troops of the 42nd Division saw extensive combat in Europe, much of the National Guard did not share this experience. The Rainbow Division saw action in every major U.S. engagement of the war, and it included Guard troops and officers from 26 total states and included many distinguished officers such as then Colonel Douglas MacArthur. (119) However, most guardsmen involved in combat operations did not arrive in France until the middle of 1918; yet, seven of the eleven divisions poised for an American advance in August were Guard divisions. (120) Other Guard divisions, such as the 34th (containing Iowa’s Guard) were not sent directly to the front, but did see some combat as reserve organizations. (121) Unlike the wartime experience of troops in the Rainbow Division, monotony exemplified life at the camps and away from the front lines, and border duty familiarized officers and troops with the monotonous lifestyle associated with camp life away from the front lines.

The monotony of camp life is apparent in the official history of the 126th Field Artillery (formerly the First Iowa Field Artillery). The 126th arrived at Fort Roots, Arkansas early in July 1917 and left for Camp Cody, New Mexico in October 1917. The official history then noted months on end which consisted of “usual camp duties.” (122) The 126th remained at Camp Cody until July 1918, when they embarked for training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, which continued for three months. The 126th arrived in France on October 18, 1918 where they once again “took up usual camp duties.” (123) The monotony of usual camp duties was seemingly only interrupted for transportation to other stations, training of a specific nature, and official reviews of the 34th Division. (124) The experience of these Iowa troops was drastically different than those of the 168th who were actively engaged in combat; however, their service was still important to the war effort because these troops provided the regular army with the reserve force necessary to carry out combat operations.

(103) Lasher, Report, 1918, 7 and Hill, Minute Man, 262-3. Though the Guard was federalized in July, it was not until August 5 when the Guard was officially drafted into the Army as it fit under the Selective Service Act. Guardsmen removed state affiliations from uniforms and replaced them with U.S. Army insignia, and Guard units were re-numbered from state regiments to national ones to fit into the new American Army.

(104) Lasher, Report, 1918, 43. Many troops who had been stationed at the border were denied active duty status during their tour in Texas, and were required to take a third oath of service. Many guardsmen refused this third oath and left the guard. Many of these who refused to take the oath were required to enroll in the selective service and were eventually drafted into the AEF.

(105) Ibid., 33.

(106) Pvt. Everett Wright, Journal, October 19, 1917, Papers of Everett Wright, 1999.33.2 Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(107) Lasher, Report, 1918, 38. and “History of Battery ‘C’ 126th Field Artillery”

(108) Adjutant General’s Report, Roster of National Guard and Naval Militia as Called for World War Service (Springfield: Illinois State Government Press, 1918) ix and Hill, Minute Man, 272 and Paxson, America at War, 316.

(109) King George V, Letter to American Troops, January, 1918, Papers of August Smidt, Correspondence, 4: 1995.131, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(110) August Smidt, Letter to Agnes, Oct 1918, Papers of August Smidt, 4: 1995.131, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(111) Cecil A. Clark Diary, December 9, 1917, Diary of Cecil A. Clark, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(112) Cecil Clark, Diary, February to March, 1918.

(113) John Kosek, editor, The Iowa Boys: A Remembrance of a Killing Contest, The Diary and Letters of Sergeant Charles Kosek Company D, 168th Iowa Infantry, 42nd Rainbow Division, American Expeditionary Force France, 1917-1918 (Copyright, Las Vegas NV 2010: Iowa National Guard Archives) 13.

(114) Alfred Bowen, Letter to Alice Woolston, July 10, 1917, Papers of Alfred Bowen, 2000.48.4, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(115) Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975) 7.

(116) Cecil Clark, Diary, May 22, 1918.

(117) General Lloyd D. Ross, Report: Fifty Germans and How They Fared, June 1918, Papers of General Ross, WWI Box, 1999.113, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA).

(118) Francis Webster, Collection of Sympathy Letters, November 1918, Papers and Items of Pvt. Francis Webster, 2005.107.30, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA). Webster was unfortunately killed only weeks before the official end of the war.

(119) Zieger, 107-8 and 42nd Division Headquarters “General Orders No 22.” Issued by Major General Menoher and written by Colonel Douglas MacArthur, Chief of Staff, Documents of General Ross, WWI Box, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge IA (Johnston, IA).

(120) Paxson, America at War, 341.

(121) Lasher, Report, 1918, 33-4. It should be noted that some of the troops from Camp Cody did eventually see line duty after being transferred out of their original units to supplement other National Guard and Army units already in the trenches.

(122) “History of Battery ‘C’ 126th Field Artillery, June, 1917” Kershenski Box, Iowa National Guard Archives, Camp Dodge, IA (Johnston, IA) 1.

(123) “History of Battery C,” 1-2. 124 Ibid., 1.

FROM

IOWA MUSEUM ASSOCIATION

French WWII Historians to Visit Red Oak 02/11/2012

March 1st, 2012-

Red Oak, Iowa will be hosting a visit from two gentlemen from France, Lionel Humbert and Philippe Esvalin. Philippe has recently written a book on pilots who flew gliders in World War Two called “Forgotten Wings”. Lionel is a avid historian especially on World War One and has a lifelong dream of coming to Iowa. Lionel lives in a small town called Neufmaison and that happens to be where the 168th Iowa Infantry first fought in World War One. Lionel and Philippe are coming to honor the American sacrifice of both World Wars and to say thank you to the American people for helping keep their country free. They are particularly interested in Iowa.

They will touring Red Oak and the area on Thursday, getting to know the community where all the Americans came from almost one hundred years ago.

March 1st, 2012-

Red Oak, Iowa will be hosting a visit from two gentlemen from France, Lionel Humbert and Philippe Esvalin. Philippe has recently written a book on pilots who flew gliders in World War Two called “Forgotten Wings”. Lionel is a avid historian especially on World War One and has a lifelong dream of coming to Iowa. Lionel lives in a small town called Neufmaison and that happens to be where the 168th Iowa Infantry first fought in World War One. Lionel and Philippe are coming to honor the American sacrifice of both World Wars and to say thank you to the American people for helping keep their country free. They are particularly interested in Iowa.

They will touring Red Oak and the area on Thursday, getting to know the community where all the Americans came from almost one hundred years ago.